This type of organism, which can consume methane in the absence of oxygen, has previously been found only in marine sediments.

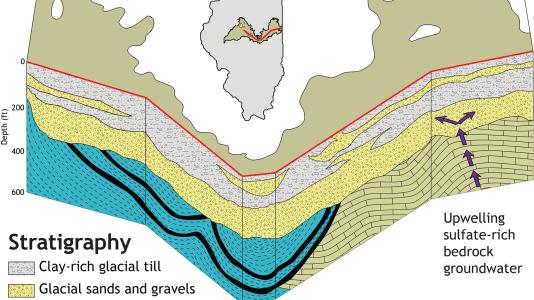

The team studied the microbial community living deep underground in the Mahomet Aquifer, a multi-trillion-gallon subterranean reservoir that provides drinking water to residents in central Illinois. It is uncontaminated by human activity.

“The problem we set out to address is that we didn’t really have a good sense of what the microbial community in a pristine aquifer looks like,” said Argonne postdoctoral fellow Ted Flynn. Microbes play an integral role in the chemical makeup of groundwater, and scientists are still teasing out their role in the global ecosystem.

The Mahomet aquifer is protected by its glacial ancestry; growing and receding glaciers laid alternating blankets of fine glacial “till” and coarser gravel. When humans spill something toxic aboveground, the silt and clay in the till layer act as a filter to delay its passage to the clean water below.

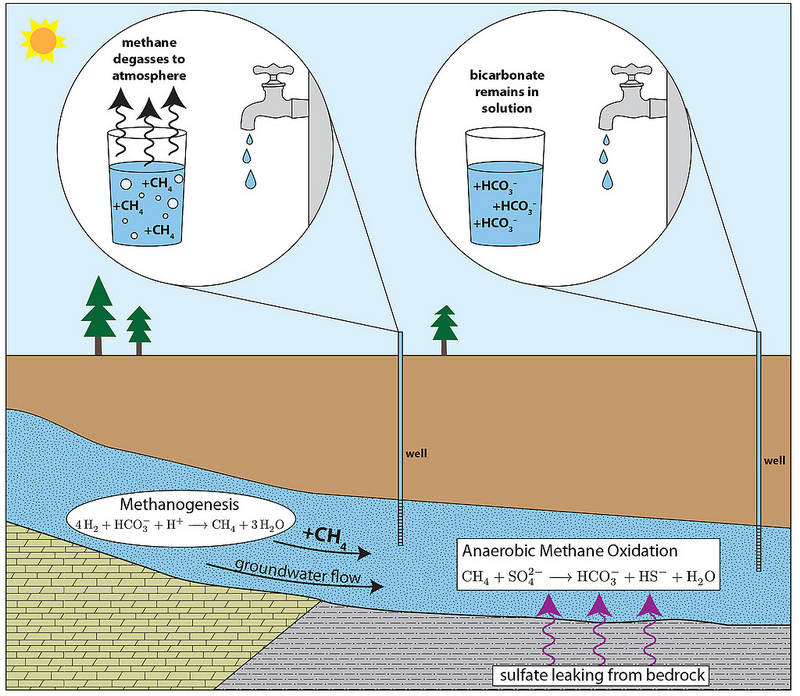

It’s also a natural hotbed of methane production. “In some parts of the Mahomet, the groundwater is so charged with methane that when you pump it to the surface, bubbles of the gas effervesce out—like champagne—and can be ignited,” Flynn said.

Flynn and his colleagues knew that most existing studies on groundwater simply catalogued the microbes in a sample of water pulled up from the aquifer. But they thought this method might not represent what lives in the solid sediment lining the aquifer’s walls and layers. So they lowered clean bags filled with sterile sediment down into the aquifer and let the microbes colonize them over three months.

This meant the scientists were sampling only live microbes that had been active in the past three months. By comparison, a sample of sediment directly lifted from the walls through a DNA sequencer would pull up DNA fragments from long-dead microbes, which wouldn’t give a clear picture of the current microbe population.

Inside the aquifer, they discovered an odd organism that had previously only been noted along deep-sea vents on the ocean floor: tiny microorganisms, called anaerobic methane oxidizers, that consume methane even in the absence of oxygen. They are archaea, which make up one of the three evolutionary domains of life along with bacteria and eukaryotes, which includes humans. Anaerobic methane oxidizers were first found living along the ocean floor near deep-sea vents, living off the methane bubbling out of the vents. “This is the first time we’ve seen them in terrestrial habitats,” Flynn said.

These organisms turn methane into bicarbonate, a compound that doesn’t leak into the atmosphere but stays dissolved in water. (You’ve probably seen bicarbonate: it sometimes reacts with metal to leave a flaky white residue on drinking fountains, Flynn said.)

The findings are discussed in the study, “Functional microbial diversity explains groundwater chemistry in a pristine aquifer,” published in BMC Microbiology. Other researchers came from the Environmental Protection Agency and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The research was supported by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation’s first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America’s scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.