This story was originally published in volume 6, issue 1 of Argonne Now, the laboratory’s biannual science magazine.

Back in the earliest days of nuclear energy, Argonne physicists and engineers used slide rules and their own basic knowledge of reactions and physics to design nuclear power plants. Then, beginning in the early 1960s, they enlisted computers to develop designs with data from experiments and actual reactor testing. Over this entire span, Argonne built over 85 experimental reactors to test its reactor designs and computer programs – each a costly and time-consuming endeavor.

Despite all this, many of the highly complex physical phenomena that affect reactor performance and safety remained somewhat of a mystery. It wasn’t possible to “see” what was taking place inside this very harsh environment—until now.

Researchers are using some of the world’s most powerful computers at the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility to take a leap forward in nuclear reactor design, analysis and engineering. Their efforts could shave millions of dollars off the cost of reactor design, development, preparation for licensing, and construction.

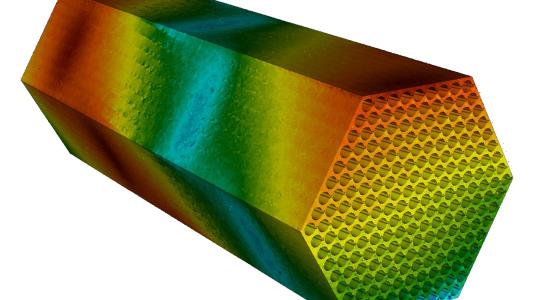

Researchers have developed a suite of computer tools, called the Simulation-based High-efficiency Advanced Reactor Prototyping (SHARP) Reactor Performance and Safety Simulation Suite, that numerically mimic and allow researchers to “see” the physical processes that occur in a nuclear reactor core. SHARP users can build complex virtual reactor models, which can run the reactor through a variety of operational or accident scenarios that would be impractical or impossible in the real world.

SHARP builds upon existing computer codes used to conduct safety evaluations of today’s aging nuclear power reactors. When you want to use those older codes to virtually test new reactors, however, you run into a few problems. They’re well calibrated for evaluating the safety of new reactor designs, but they aren’t so great for optimizing designs for efficiency or cost. SHARP has been written specifically to simultaneously look at the safety, lifetime, and performance of different advanced design ideas.

Idaho National Laboratory, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and other U.S. DOE and university collaborators have also contributed to SHARP.

This is a perfect fit for Argonne’s nuclear program, which has a half-century of experience with reactors under its belt and one of the world’s largest concentrations of researchers involved in advanced reactor design. For example, early in the program, the code creators wanted to test how accurate the codes could be. They built a virtual model of one of Argonne’s historical test reactors, the Zero Power Reactor, ran “experiments” on it and checked how well the computer results matched up against the actual data.

Modern codes like SHARP are already successfully replacing some types of nuclear experiments. SHARP’s next step is refining the code to make it run more efficiently on powerful supercomputers like Argonne’s new Blue Gene/Q. More efficient codes mean scientists can run more tests during the same computer time with fewer problems, making SHARP a more useful tool for reactor designers around the world.